What is a fast movement in biology?

In the blink of an eye?

Is an eye blink really that fast? Our informal glimpse of 18 departmental members who blinked in front of our high speed video filming at 125 frames per second, showed that an average duration eye blink is 0.27 seconds. Fast? Not really. A mantis shrimp’s raptorial strike occurs within 3 milliseconds (thus one might fit 90 strikes into a single eye blink – although the animals do not actually repeat the strikes this quickly). So, what is an extremely fast movement in biology? The answer to that question is the goal of this page. More generally, how organisms generate these extreme movements also happens to be a primary interest of our laboratory.

Fast movements in biology

There is an inherent fascination with extremes in biology. One particular fascination is the attempt to find the fastest organism on the planet. It turns out that this is not as simple a question as it may seem. What does one mean by “fast”? And, how would we know if an organism is the fastest on the planet? The goal of this page is to help tease apart the relevant questions and offer a few answers to these questions.

What does “fast” mean?

When we refer to a fast movement, several parameters might be relevant:

– duration of movement (e.g., seconds),

– speed of movement (e.g., meters per second), or

– acceleration of movement (e.g., number of g’s or meters per second squared).

Some animals achieve high speeds with a low acceleration and over a relatively long time period. Examples include cheetahs, sharks, kangaroos and falcons. All of these animals gradually build up high speeds by repeated contractions of body musculature.

Some organisms achieve short duration movements through high accelerations, but never achieve particularly high speeds. Some examples include nematocysts (stinging cells in jellyfish) and exploding fungi. In these organisms, the acceleration is extremely high, but the duration is so short that high speeds are never achieved.

Other animals achieve high speeds through high accelerations and short-duration movements. Examples include mantis shrimp, trap-jaw ants, snapping shrimp and termites.

How are fast movements achieved?

Even the fastest muscles are slow. Animals relying solely on muscle power output to generate high speeds require a long, slow acceleration to reach those speeds. Therefore, kangaroos, cheetahs and sharks take a comparatively long time to build up to high speeds. They also use elastic structures in their bodies to make their movements more efficient.

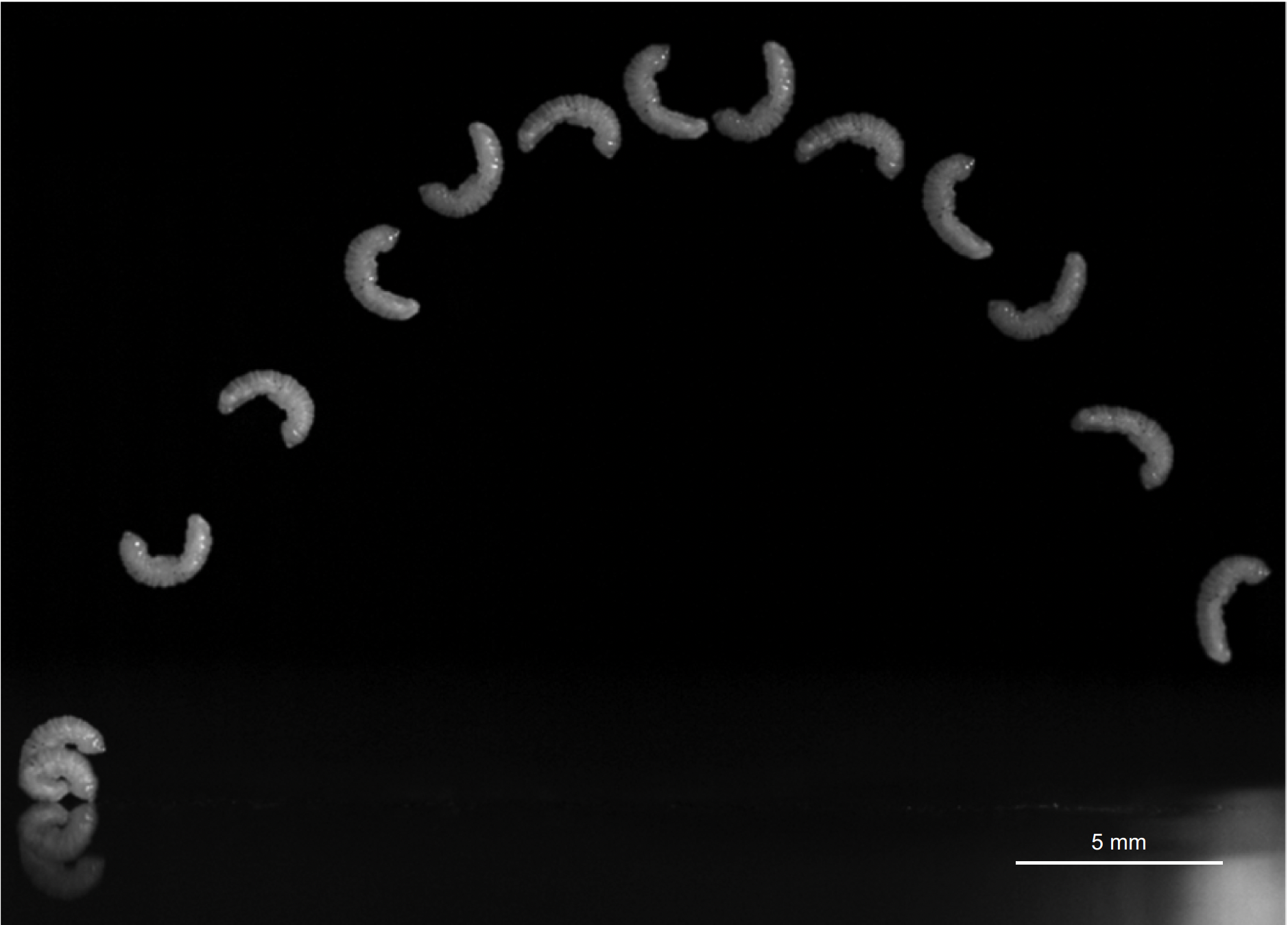

Many animals circumvent the limitations of muscle contraction speed by using springs and latches, rather like a cross-bow in which the energy is stored prior to the arrow’s release. With a cross-bow, one uses the arm’s slow muscles, and then the stored energy is released extremely rapidly with a latch or trigger. This phenomenon is called power amplification and it is used by trap-jaw ants, mantis shrimp and termites.

Many organisms do not have muscles available to generate high speeds. For example, fungi use surface tension energy to drive the spores off their “stems” (sterigma) over short time periods. Cnidarian nematocysts use high pressure capsules to fire their microscopic poison daggers.

What is the fastest organism?

Looking at peak sustained speeds – cheetahs might be the fastest. Or, focusing on peak unpowered speeds, diving falcons may be the fastest. On the other hand, if duration of the movement were the criterion of interest, nemtocysts and fungal spores would be the fastest. Lastly, considering acceleration of an appendage relative to the body through power amplification, then trap-jaw ants and termites come out on top.

But, perhaps the most important issue is whether scientists have actually measured the fastest organisms on the planet. The only known systems are the organisms that have been measured…there may be faster ones that have not yet been discovered!

For our latest papers on this topic, check out our Google Scholar, Research Gate, or Orcid pages.

For a general overview of recent discoveries and principles of extremely fast movement in mantis shrimp and other creatures, see:

Patek, S. N. 2015. The most powerful movements in biology. American Scientist 103(5): 330-337.

For a conceptual and mathematical framework of small, fast systems, see: Ilton et al. 2018. The principles of cascading power limits in small, fast biological and engineered systems. Science 360 (6387). DOI: 10.1126/science.aao1082